”As more commerce moves into the realm of digital bits, laws built around a world of atoms will be challenged

Osborn[1]

1. Introduction

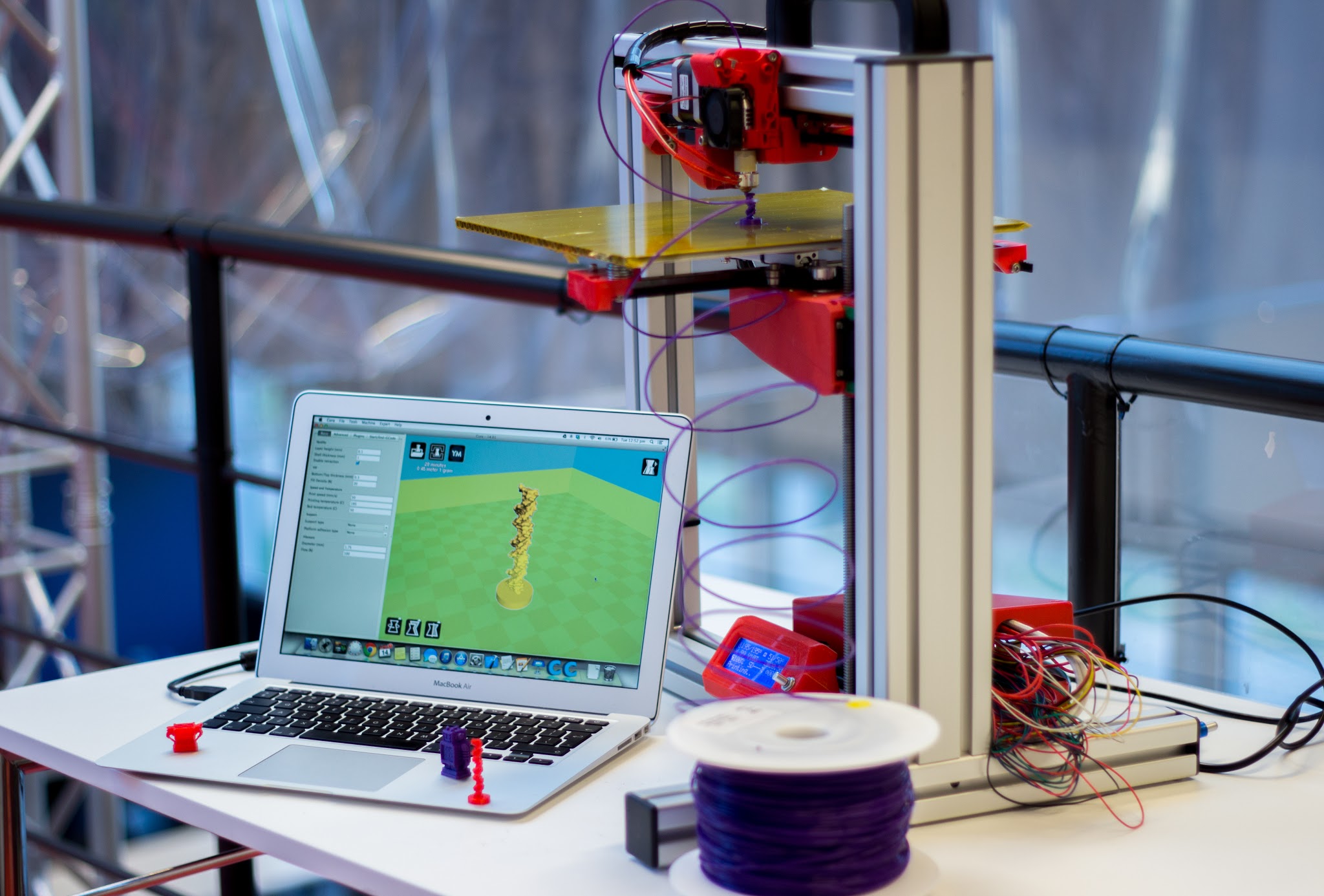

Toys, jewelry, appliance parts and auto-generated printers; clothes, food[2] and houses; medicines, dental prostheses[3] and lung tissue. Across the spectrum from the ridiculous to the sublime these are just few example of what 3D printers have the potential to create on the cusp of the next great industrial revolution[4]. If not now, soon enough, it will be possible to digitize almost anything and then turn it into physical objects only by pressing a button. After the digital revolution has determined the shift from atoms to bits, 3D printing (hereinafter, “3DP”) has the potential to turn bits in atoms in such easy way to not only threaten the industries based on traditional manufacturing methods, but also to destabilize the legal framework and constructs developed over the centuries around a world of atoms – which is now being disrupted[5]. Moreover, it is impossible to fully predict the ways in which this technology will be used (and abused) in the “factories of the future”[6] and in the houses of “prosumers”[7]. Whether 3DP constitutes a threat to contain or an opportunity to modernize the law – especially trademark law – is a separate issue.

How traditional manufacturers and trademark holders should deal with such challenge is addressed in section IV of this paper, after having described the functioning and the current level of market penetration of 3DP, its impact on the traditional paradigm of manufacturing and delivering goods (section II) and the legal issues raised, especially for trademark law, by such new tool of “decentralized piracy”[8](section III).

2. 3DP and the democratization of production

The origins of 3DP trace back to the patent obtained by Wyn Swainson in 1977 for laser beams to manufacture tridimensional objects[9] and to a wave of patents subsequently registered [10] in relation to the so-called process of “additive” manufacturing, i.e., the process of accretive creation of products by adding many thin layers of material – whether metals, plastics or even organic tissues – one upon the other[11]. The printing instructions are contained in electronic Computer Aided Design (“CAD”) files, which play a fundamental role in the conversion of digital to physical: CAD files map the geometries of any object, generate digitized cross sections of the virtual model and serves as a digital blueprint model in the manufacturing phase [12].

While in the 1980s, research efforts were mainly focused around prototyping for design, in the last 15 years the attention has shifted to customer product manufacturing and 3DP has now gained both a significant legal and commercial importance[13]. The largest market segment currently embracing 3DP is that of industrial applications, while 3DP has not yet penetrated the mainstream market of consumer population due to barriers concerning difficulty of use, high prices, low quality of the printed outputs in comparison to those manufactured through traditional processes and unfamiliarity of the general public[14].

However, such barriers are expected to be overcome and 3DP to attain rapid growth numbers[15], due to spontaneous market forces, but also thanks to specific measures implemented and investments made by institutional actors (e.g., the European Union[16]). Items will soon be mass-produced by means of 3DP and CAD files increasingly made available online by commercial websites or in file sharing networks[17].

In this way, 3DP will be the heart and should of what may be considered the third industrial revolution[18]: it will revolutionize the paradigm of manufacturing and delivering goods and this will have an impact on intellectual property law as well. While under the traditional model «if you build it, then the consumer will come»manufacturers produce goods, file trademarks to protect their source of origin and establish manufacturing facilities and complex supply chains around the world for their delivery, in a 3DP world the consumer is both the producer and the end-customer.

The democratization of creation enabled by 3DP will eliminate both the barriers to entry in manufacturing and the need to rely on the distribution function[19]. Anyone will be able to produce almost anything away from the control of the traditional manufacturing and delivering operators. Without product sales, not even governments will be able to collect sales taxes, customs duties or enforce embargoes[20]. The possibility to bypass the traditional supply chain and self-manufacture will also determine the shift from mass production to mass customization, a change in business models and the development of a new ecosystem surrounding 3DP[21].

While new business entities enter the market to capture this new way of creating value, the very companies that might be most at risk could maintain their competitive edge by getting ahead of this wave and by considering 3DP as an opportunity to better serve their base of customers through software-driven and customization-enabling infrastructure, as well as value-added services[22].

The same proactive – rather than protectionist – approach should be adopted by the IP right-holders upon realizing that the democratization of production and mass-customization make IP rights, including trademarks, lees effective and more infringed. Consequently, in comparison to the past, new business models that rely less on IP rights and enforcement should be pursued, exactly as it has happened with the music and movie industries[23].

3. The struggle of trademark law in the world of 3DP

The intersection between IP rights and 3DP may result into a two-way disruption, with IP disrupting the progress of 3DP and 3DP «relegat[ing] some IP rights to the scrap heap»[24]. However, as for the first scenario, restricting technological advancements would be detrimental for the welfare of the entire collectivity. It would also encourage circumvention measures and the creation of a black market. In the second scenario, the democratization of production away from control triggers the risk of the “Five Is”: (i) infringement, that becomes extremely likely when anyone can 3D print almost any product with any trademark on it, reproduce three-dimensional marks or manufacture 3D versions of 2D trademarks; (ii) identifiability of infringement, that becomes harder; (iii) impracticability or (iv) impossibility to enforce IP rights against the infringers; and (v) the consequent irrelevance of IP rights[25].

Such irrelevance and the lessened value of IP rights may also be explained in light of the fact that IP needs to artificially impose scarcity to be relevant, whereas 3DP enables zero marginal cost production and fosters a «post-scarcity» world characterized by mass creation and mass distribution. Consequently, IP rights are deemphasized[26].

The above-mentioned issues, including the increasing likelihood of infringement and counterfeiting, affect trademark as well. In particular, the possibility to produce goods with any company’s trademark on them causes (i) search difficulties, given the resemblance between the traditional manufacturers’ authentic goods and the 3D printed ones; (ii) deception, due to the likelihood of confusion, which would lead to more purchasing mistakes; (iii) weakened communication, when 3D-printed goods resemble traditionally manufactured goods but carry an inherent message different from the one of the traditional manufacturers; (iv) erosion of the value of traditional manufacturers’ trademark assets; (v) devaluing Internet-based business models, since consumers will find more convenient to access CAD files than the traditional business-to-consumer website functions[27].

Moreover, the surge in 3DP impacts on the very function and raison d’êtreof trademarks, that is that of serving as source identifiers and seal of authenticity for consumers, by legally representing entities by their goods and services, as well as providing an implied guarantee of consistent quality and ensuring less search costs and no risk of confusion for consumers[28]. In other words, without trademarks «[t]here could be no pride of workmanship, no credit for good quality, [and] no responsibility for bad»[29]. But in a 3DP world trademarks ability to connect a good to a source is less relevant since consumers themselves produce the goods and therefore are perfectly aware of their origin. On the other hand, consumers will no longer be able to infer the quality of a product and its social status just by quickly observing a trademarked product in a post-sale environment[30].

In the meanwhile, the claim that 3D-printed goods are of lower quality is losing support over time.

In other words, 3DP «alters settled assumptions about manufacturing, design, and trademarks and thus precludes simplistic application of current trademark doctrine»[31]. Similarly to previous technological innovations, this may catalyze doctrinal changes to the law[32], but it should also prompt the adoption of different business strategies.

4. Choosing branding strategies over retaliatory trademark measures

Traditional manufacturers of goods could draw from their arsenal a number of response strategies, including lobbying and retaliatory legal action or threat thereof, implementing digital rights management (“DRM”) technologies, recurring to cease and desist letters and demanding the cooperation of online intermediaries in blocking websites hosting potentially infringing contents[33].

However, since «you can’t sue the genie back in the bottle»[34], traditional manufacturers and trademark holders would be better suited to invest into non-IP-rights-based business models and building brand value through branding strategies aimed at retaining the existing base of customers, while at the same time engaging new 3DP enthusiasts and combining the current consumer engagement models with 3DP applications and services[35].

In fact, given the lessened identification function of trademarks in the 3DP ecosystem, traditional operators should rather exploit the emotional and symbolic appeal that brands have over consumers[36]. Accordingly, scholars should dedicate more efforts to brand scholarship, which has been under-theorized so far[37]. Even without going so far as to suggesting that trademarks constitute a subset of brands[38], it should be taken into due account that brands reflect technological progress and the culture of people of a time and place and therefore may play a significant strategic role[39].

In contrast to trademarks[40], brands do not just identify and distinguish the name or the products of a business, but are fundamental in generating emotions and building a relation of trust with consumers. Consequently, they are better suited to the participatory culture inherent with 3DP, which is close to that of the web 2.0.

While in the past launching a brand required costly investments throughout the distribution chain, in a 3DP world branding strategies can be pursued through low-cost information exchange mechanisms. In order to promote a fruitful dialogue with consumers and foster their brand engagement, such branding strategies should focus on the following: (i) authentication, i.e. the offer by traditional manufacturers of «official» CAD files to consumers; (ii) personalization, i.e. enabling highly-customizable products; (iii) creativity, i.e. promoting creative and co-creative experiences; and (iv) community, i.e. creating 3DP communities to encourage brand engagement[41].

Similarly, it has been suggested to structure marketing strategies on the following pillars: (i) peer-production, i.e. a system of social, decentralized production[42]; (ii) personalization; (iii) physibles, defined as digital printable items; and (iv) prosumers[43], i.e. proactive consumers engaged in both production and consumption – that therefore should no longer be considered two separate streams – and who are willing to promote and further develop a brand[44].

5. Final remarks

Gutenberg’s turned the world upside down by enabling mass production of the printed word, a trend that was later expanded and furthered by the industrial revolution. Now 3DP technologies may invert this mass production model by enabling decentralized production one item at a time. At the same time, the democratization of production and the high degree of customizability may well be interpreted as a response to Marx’s claim that mass production alienated workers from the means of production and had depersonalization effects[45].

Besides the historic and socio-economic aspects of the phenomenon, it has been demonstrated that the legal challenges raised by 3DP are significant and intriguing.

Traditional manufacturers and trademark holders should not try to obtain greater protection through lobbying and stop infringers by suing them, but should take away the incentives to infringe by releasing CAD files of their own and invest in branding strategies that foster brand commitment and participatory forms of production. More generally, in order to remain relevant in such changing world, they should embrace the economic opportunities brought by the 3DP revolution, mindful that «no, the market will not always stay the way you like it. Occasionally, however, it will tell you exactly where it’s going and how to exploit it»[46].

Similarly, rather than keep stretching trademark law to stifle a nascent technology, a «move from the realm of logic to the realm of emotion»[47]is suggested: the very rationale of trademarks should be re-evaluated and more attention should be dedicated to brands. In addition, any legislative intervention[48]should move towards user-friendly resolutions that protect the interests of trademarks holders without stifling the social and economic benefits of 3DP[49].

It is undeniable that 3DP can ensure higher quality products, continuous innovation and a better world for humanity. In a world where the quality of life is defined by wealth, low-income families should be given the opportunity to manufacture a better life for themselves. That is how a 3D printer becomes «[a] prosthetic leg in the hands of an African child, a liver transplant for a Hepatitis patient, or a home for a family that lost everything to a flood»[50]. In other words, «[t]he 3DP revolution is where technological potential meets this desire to better the world. Out of this union, wonders can come, but change can only come if the legal system allows it»[51].

[1]OsbornL.S., Trademark boundaries and 3D printing, 50 Akron Law Review, 2016, 865-902: 866.

[2]Tran J.L., 3D-printed food, 17 Minn. J.L. Sci. & Tech., 2016, 855-880.

[3]On this, see the Judgement of the Italian Court of Vicenza n. 1686/2015.

[4]For a detailed overview of the most notable products created with 3D printers so far, see CouchJ.L., Additively manufacturing a better life: how 3D printing can change the world without changing the law, 51 Gonz. L. Rev., 2015, 517-544: 519-527.

[5]The theory of disruptive technologies was developed by BowerJ.L. and ChristensenC.M. in Disruptive technologies: catching the wave, Harvard Business Review, 1995.

[6]European Economic and Social Committee, Living tomorrow. 3D printing: a tool to empower the European economy, Opinion 2015/C, 332/05 (the “Opinion”).

[7]See paragraph IV.

[8]DepoorterB., Intellectual property infringements & 3D printing: decentralized piracy, 65 Hastings L.J., 2014, 1483-1504.

[9]U.S. patent no. 4041476.

[10]Among them, the U.S. patent no. 4575330 obtained by C.W. Hullon 11 March 1986 for what he called “stereolithography”. MoskinJ., Roll over Gutenberg. Tell Mr. Hull the news: obstacles and opportunities from 3D printing, 104 Trademark Rep., 2014, 811-816: 816.

[11]In contrast, more traditional manufacturing processes have a subtractive nature: material is not added, but removed, through techniques like cutting or drilling. MatiasE., RaoB., 3D printing: on its historical evolution and the implication for business, Proceedings of PICMET: management of the technology age, 2015, 551-558: 551.

[12]WeinbergM., It will be awesome if they don’t screw up: 3D printing, intellectual property, and the fight over the next great disruptive technology, Public knowledge, 2010, 3-4. GibsonI. et al., Additive manufacturing technologies: 3D printing, rapid prototyping, and direct digital manufacturing, Springer, 2015.

[13]WilkofN., Trademarks and brands in the competitive landscape of the 3D printing ecosystem, 104 Trademark Rep., 2014, 817-821: 817.

[14]EbrahimT.Y., 3D printing: digital infringement & digital regulation, 14 Nw. J. Tech. & Intell.Prop., 2016, 37-74: 6-7, 15.

[15]Wohlers Associates, 3D printing and additive manufacturing: state of the industry, Annual worldwide progress report, 2016.

[16]See the Opinion, cit., for a list of measures to be adopted at the European level to reach the full potential of 3DP. To identify such measures the European Economic and Social Committee referred to, inter alia, the report of Roland Berger Strategy Consultants, The industry 4.0. The new industrial revolution: how Europe will succeed, 2014.

[17]For instance, the renowned file-sharing website Pirate Bay has already launched the new category of “physibles”. Toniutti T., Pirate Bay lancia i “Physibles”, oggetti reali da stampare in 3D, La Repubblica, 2.2.2012 (http://www.repubblica.it/tecnologia/2012/02/02/news/pirate_bay_lancia_i_pysbles_oggetti_reali_da_stampare_in_3d-29087296/).

[18]The Economist, A third industrial revolution, 21.4.2012 (http://www.economist.com/node/21552901). See also Hopkinson N. and Hague R.J.M. (eds.), Rapid manufacturing: an industrial revolution for the digital age, John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

[19]ManyikaJ. et al., Disruptive technologies: advances that will transform life, business, and the global economy, Mckinsey Global Institute, 2013: 110-111.

[20]HornickJ., 3D printing and IP rights: the elephant in the room, 55 Santa Clara L. Rev., 2015, 801-819: 804-805.

[21]According to Ebrahim, cit., 9-10, the following business entity types will dominate: (i) the manufacturers of 3D printers and equipment, which represent the hardware backbone for the entire ecosystem; (ii) printing intermediaries, working as printing service bureaus, printing hubs, Print as a Service (“PaaS”) entities or print-on-demand services; (iii) the providers of software tools; (iv) e-commerce websites and repositories of CAD files; and, (v) providers of information technology and service oriented solutions utilizing 3DP. For a similar reconstruction see Wilkof,cit., 817-818.

[22]Moskin, cit., 812; Hornick, cit., 804.

[23]Couch, cit., 531-534; Depoorter,cit.; ScardamagliaA., Flashpoints in 3D printing and trademark law, 23 J. L. Info. & Sci., 2015, 30-54.

[24]Hornick, cit., 802.

[25]Id., 806. For an analysis tailored to Italian trademark law see GalliC. and ContiniA., Stampanti 3D e proprietà intellettuale: opportunità e problemi, 1 Rivista di diritto industriale, 2015, 115-151.

[26]LemleyM., IP in a world without scarcity, 90 New York University Law Review, 2015, 460-515: 462.

[27]Ebrahim, cit., 22-23.

[28]BiagioliM. et al, Brand new world: distinguishing oneself in the global flow, 47 U.C. Davis L. Rev., 2013, 455-457. SchechterF., The historic foundation of the law relating to trademark, Columbia University Press, 1925.

[29]RogersE.S., The Lanham Act and the social function of trade-marks, 14 Law & Contemp. Probs., 1949, 173-184: 175.

[30]GraceJ., The end of post-sale confusion: how consumer 3D printing will diminish the function of trademarks, 28 Harv. J. L. & Tech., 2014, 263-288. SonmezE., Cottage piracy, 3D printing, and secondary trademark liability: counterfeit luxury trademarks and DIY, 48 U.S.F. L. Rev., 2014, 757-792: 757-758.

[31]Osborne, cit., 867.

[32]SurdenH., Technological cost as law in intellectual property, 27 Harv. J. L. Tech., 2013, 135-202.

[33]Depoorter, cit.; Sonmez, cit.

[34]Couch, cit., 531.

[35]Ebrahim, cit., 4, 36.

[36]Id., 22, 37.

[37]Resai D.R., From trademarks to brands, 64 Fla. L. Rev., 2012, 981-1044.

[38]Id., 1043

[39]Biagioli, cit., 459.

[40]Although the terms “trademark” and “brand” are often used interchangeably, they are not the same. As specified by WIPO, in The role of trademarks in marketing, WIPO Magazine, 2002, 10-11, «a product brand or a corporate brand is a much larger concept than a mere trademark, as building a strong brand and establishing the brand equity of a business is a bigger challenge than choosing, registering, or maintaining one or more trademarks. Strong brands and successful branding generally refers to successes in terms of contribution to market share, sales, profit margins, loyalty and market awareness». On this, DavisJ., Between a sign and a brand: mapping the boundaries of a registered trademark in European Union trademark law, in BentlyL. et al. (eds.), Trade marks and brands: an interdisciplinary critique, Cambridge University Press, 2011: 65-91.

[41]Ebrahim, cit., 42-43.

[42]On this, BenklerY. et al., Peer production: a form of collective intelligence, in MaloneT.W. and BernsteinM.S. (eds.) Handbook of Collective Intelligence, MIT Press, 2015.

[43]RitzerG. and JurgensonN., Production, consumption, prosumption: the nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’, 10 Journal of Consumer Culture, 2010, 13-36.

[44]Ebrahim, cit., 48-52.

[45]Moskin, cit., 816.

[46]RoyD., 3D printers and what it can mean for patent holders, Tactical IP, 15 February 2012.

[47]Biagioli, cit., 472.

[48]Arguments for direct regulation of 3DP to address infringement but also public policy questions relating to firearms and drugs in ReddyP., The legal dimension of 3D printing: analyzing secondary liability in additive layer manufacture, 16 Colum. Sci. & Tech. L. Rev., 2014, 222-247.

[49]DagneT.W., The left shark, thrones, sculptures and unprintable triangle: 3D printing and its intersections with IP, 25 Alb. L.J. Sci. & Tech., 2015, 573-592: 587-591.

[50]Couch, cit., 543.

[51]Id., 527.